Reduction in Force

Or How I Got Fired by a Car Salesman*

It’s not especially easy to get a research job with the federal government. If you’re an economist, you spend six years in a PhD program proving fixed point theorems and getting pilloried on Rate My Professor.1 Then you put in something like 1,000 applications all at once in a centralized job market. You hope that some of those turn into offers someplace not a three-day ride by ox cart from the nearest train station. Then you might find yourself working for the government or a university. In my case it was the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which I was quite excited about. I got to do research, and I got to work with a nice group of colleagues genuinely invested in and curious about our work.

I was hired into a research group created by Mr. Trump’s first director on the theory that, to regulate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, it would be good to have a few economists around who understood housing and mortgage markets. We pitched and conducted research we thought would be of use to the agency. When edicts came down (say, “answer this” or “put together a project with that group”), we followed them. I’m sure we all had our political opinions (have you ever met an economist who didn’t?) but I think we all took pride in our jobs. We were nonpartisan as far as work went. It was almost neurotic how careful everyone was to avoid violating the Hatch Act, ironic given reporting on the Trump administration’s complete disregard for it.

During our team meeting immediately following Mr. Trump’s election, my supervisor focused on how best to anticipate what the incoming administration might want from us. We were told to wrap up any papers relating to climate change (flooding, say, is of interest for anyone studying mortgage risk) and to think about projects pertaining to housing supply and potential Fannie/Freddie privatization. In short, we went through the sort of boring change of priorities you might have with any new boss. And we worked with that in mind until the end of the Biden administration.

In the days following the inauguration, I suddenly became a censor. Old research papers dating back years were pulled down from the agency’s website for revision. It became clear that whoever was ordering the changes was just doing a keyword search. We were given a list of words to expunge. I quipped to a colleague that one thing zealots all have in common is that they get very upset with normal people who use “sex” (the allowed word) and “gender” (the forbidden one) interchangeably.2 “Race” was also off limits. It’s often used as a control variable in papers that have nothing to do with race. We had to replace it with, “demographics.” “Bias” was a tricky one to go without. It’s a technical term in statistics (a biased estimator is one that’s off predictably) without a direct synonym. I felt like Ampleforth in 1984. One could say an estimator is “off base,” but it’s a bit like describing a tachometer as, “that gauge in the dashboard that swings around when the car goes vroom”. Once all the no-no words were removed, papers could be reposted. The whole process was doubly annoying because no one would put anything in writing. So, instead of just getting an email explaining what we were meant to censor, the deputy director called someone, who called someone, who called us to play some game of telephone. Then, if we interpreted vague instructions correctly, they’d leave us alone. If not, they’d tell us that there were still bad words in our work, but we’d have to guess which ones and try again.

My agency was, nominally, independent but it seemed they were going above and beyond in trying to obey the flurry of executive orders. Telework was completely revoked. It wasn’t entirely clear whether this violated agreements with the union, but my union isn’t very good at its job, so that didn’t matter. Probationary workers were to be fired but my group actually didn’t lose ours since economists had been classified as “mission critical”. At some point people got mad that USAID, in between subversive activities like giving grain to starving children, had purchased a Politico subscription. This triggered orders for us to cancel any subscriptions to Politico, the New York Times, and Bloomberg News. Amid all this, I found it annoying that OPM emails very pointedly came outside of business hours (like 2:00 am on a Saturday) as something of a dig at anyone who had a life outside the office.

Our union, the NTEU, held a meeting about all of this in February where they made very clear they had no idea what they were doing. A flummoxed lady kept repeating, “we’re doing everything we can” like a mantra. When someone inquired as to specifics, she responded, “you can keep asking but the answer will not change: we’re doing everything we can.” Everything they can do apparently entailed complaining they weren’t given notice about policy changes and sending emails ending with “in solidarity”. (Also, post-firing, they continue to ask me for more money.)

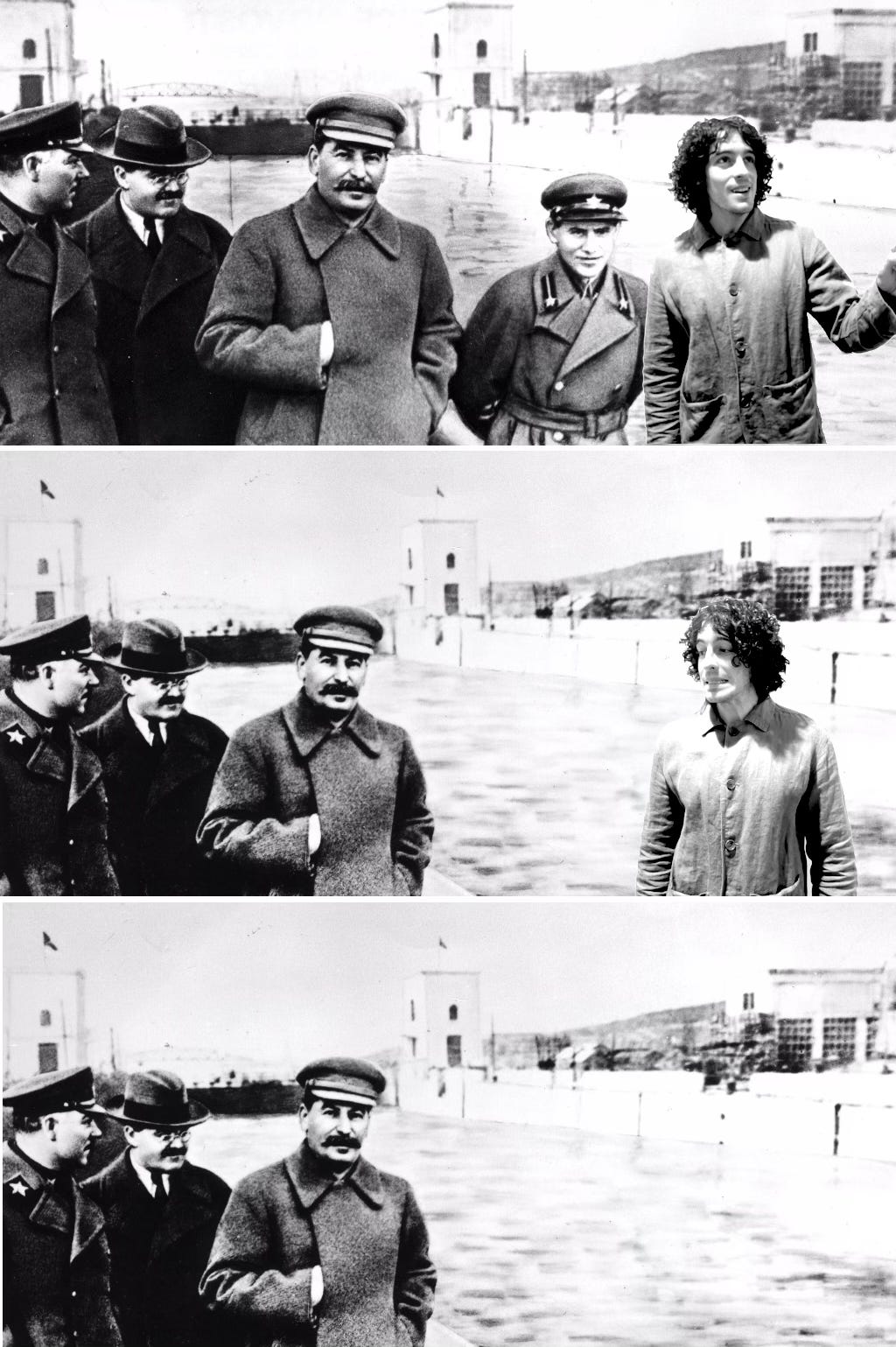

I suppose I started worrying when the DOGE people began tearing through the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) since we shared a building. [edit: We did not and I was wrong about it for three years. For some reason I was so sure I saw their seal hanging in the building.3] For our part, research papers were pulled down again. Any mention of the CFPB had to be stricken (they managed some datasets so were only ever mentioned as a citation). It was a bit like versions of a photo of Stalin with progressively fewer buddies by his side. One Friday our data server went down for a while. We’d gotten our very own DOGE commissar, reportedly one Michael Mirski4 but I never saw who it was personally.

The rumors were that our DOGE wunderkind started giving orders to the acting director and that he threw a tantrum to the White House anytime he was refused permission to something. But, who knows what was going on? There were no official announcements, and speculation from people paranoid about losing their careers isn’t always the best source of information. I do know that they started cutting contracts pretty aggressively. The rubric was to take something (say access to a dataset) then ask management, “would your agency fall apart without this?” Of course, the answer is “no” for any individual item, so they started slashing everything. That you could apply the same logic to any particular load bearing column in a building but not all of them simultaneously didn’t seem to matter. There was talk of ripping out the coffee machines and microwaves (it was never explained how paying a janitor to throw out an already purchased coffee machine would save money). To boot, cutting staff and contracts at my agency doesn’t even save any money. It’s not funded by congressional appropriations so they could’ve locked us all inside and burned the building down and the government wouldn’t have saved a dime.

My group did our best to keep our heads down and be productive. We figured that, were we to be targeted in a reduction-in-force (RIF), we had until mid-April, then a 30-day notice period. Moreover, our nominee for director, Bill Pulte, was something of an unknown entity. We hoped that, if confirmed, he might dial back some of the DOGE stuff. He seemed relatively normal in his senate testimony. Of course, he also loved meme stocks and claimed to be the “inventor of Twitter philanthropy” so I wouldn’t say I was totally at ease.

Once Mr. Pulte was confirmed, staff expected he might drop by the office the next day, but no one saw him. He did a photo op about working through the weekend with a laptop and a stack of bar graphs I’m sure weren’t printed up solely for the photo. I expected an all-hands meeting or at least an announcement wherein our new boss introduced himself. Yet nothing was forthcoming. He did, however, immediately start firing people at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac before appointing himself chair of both companies, despite that being illegal as far as I can tell.5 He might’ve considered Lord Governor of L’Enfant Plaza while at it. In fact, at some point, he did start calling himself “director of US federal housing” (perhaps “FHFA director” is too much of a lateral move from “inheriting a homebuilding company and being active on Twitter”).6

The next Tuesday a division called the Office of Public Interest Examinations was placed on administrative leave as a precursor to getting cut in the agency’s upcoming RIF. I wasn’t surprised since they did have DEI-sounding themes in their remit. But it felt cruel. The members there weren’t necessarily idealogues and didn’t even necessarily choose the assignment. The division was created by the previous director. It could have been dissolved while transferring the staff.

Wednesday was our turn. So much for “mission critical”. An invite for “Urgent Meeting” popped up on all our calendars with a couple minutes’ notice. We all shuffled into a canteen, knowing what was about to happen. Our deputy director, ostensibly there to can us, was too choked up to speak. She was either very sad about it or it was a convincing act. She’d either dug our graves to save her own position or was just unable to convince the DOGE guy to keep us around. Or something in between. Rumors ran the gamut, and, dear reader, if you’re expecting me to describe suddenly getting clear information or official answers to anything, you’re in for some disappointment.

Some lady from HR started announcing that we were all being placed on administrative leave, with no further information to be given. Also that we shouldn’t talk to anyone about it. It almost certainly meant we were on the RIF lists, which had theretofore been secret. We were to be allowed five minutes to pack up our offices. Meanwhile, this little exercise was periodically interrupted by people dropping by the refrigerator for a snack. In a building with dozens of conference spaces and an auditorium, our HR team had not bothered to reserve a room. Nor did any of them think it might make sense to stand by the side door to prevent people from wandering in unintentionally. I asked one of the HR people about the legality of putting us on admin leave indefinitely; she responded to the effect of, “well, you’re welcome to hire a lawyer and sue if you don’t like it,” which was fun to hear from the team who’d given us hours long sermons on ethics when we were hired. We were escorted outside. All without so much as an email from the new director.

We languished on administrative leave for a while before they reached out to tell us we were being fired. They gave us a choice between being in the RIF or signing Elon Musk’s stupid “fork” agreement. Our ever useful union called a meeting to inform us about the choice, scheduled for just after the deadline for making a decision. I had another job offer at that point, so I accepted it and signed the agreement. In a way I suppose I’m lucky; getting purged in some silly stunt puts me in the company of literal rocket scientists, FBI agents, people delivering antibiotics to tubercular children… and I guess Big Bird. I should be proud to be included.

* The car salesman is also a bad father, a reported drug addict, a weirdo, someone who says things like “I am the alpha in this relationship” while looking like a pudgy Keebler elf on chemotherapy, and an all around goober.

“Costa is weird and awkward”, probably true. “Avoid this class at all Cost-a”, actually clever.

I know, I know, sex and gender are not the same thing. Sex is biological and is a genetically determined binary characteristic; gender is a related social construct. Males may be feminine for instance. Or, in gendered languages, a feminine noun is not one that “produces large gametes” (though it would be interesting if a biblioteca laid eggs). But! In the context of a research paper where you’re using a 0-1 variable to categorize the person who filled out a form, it’s pretty clear what you mean whether you put “sex” or “gender” as the row title in a table.

In my defense, we did share a building with the OCC and the FTC, which, like the CFPB, have stylized old timey scales in their logos.

The Wharton School being, of course, famous for producing fight-the-system populists who wage war on bourgeoisie government statisticians for the benefit of the working man.

Though, who knows? Maybe in legalese “The Director and each of the Deputy Directors may not — hold any office, position, or employment in any regulated entity or entity-affiliated party” means “they may, in fact, do that”. Or, maybe “Chairman of the God Damn Board” doesn’t count as a “position”. I’m too small-minded to truly understand these things.

He’s also, apparently, enough of a jackass that the Treasury Secretary threatened to punch him in the face, which is a line that sounds like it’s from Abe Simpson. He spends his days evidently baselessly accusing Federal Reserve officials of mortgage fraud because, I can only assume, he thinks it would be a good thing if Trump could replace Fed officials with idiot hacks, set interest rates too low, and cause high inflation. Americans love high inflation, which is why Jimmy Carter is being carved into Mt. Rushmore.